CHENNAI: Anubhav Sinha, known for fancy thrillers and at least one superhero film with Shah Rukh Khan, has in his latest outing given us an extraordinarily disturbing work, “Mulk.” A brutal look at the kind of Islamophobia now sweeping across the world, India especially in recent years, the movie explores this through the microcosm of a Muslim family living in Banaras, considered to be one of the holiest Hindu cities.

”Mulk,” though, begins on a very different note – with beautiful camaraderie between the family of Murad Ali Mohammed (Rishi Kapoor) and his essentially Hindu neighbors. This solidarity even includes an avowed vegetarian eating meat on the sly during Murad Ali’s 65th birthday bash. As the joyous celebration rolls on, there is little indication of the dark clouds hovering.

When Murad Ali’s nephew, Shahid (Prateik Babbar, son of the late Smita Patil), is found to be a terrorist, having bombed a bus and killed 16 innocent people, lines are redrawn and cracks begin to appear in what once seemed like such a friendly neighborhood.

Murad Ali is ostracized by the very people who had adored him and his family, and the cops arrest Shahid’s father, Bilal (Manoj Pahwa). An engaging courtroom drama follows, in which Aarthi (Taapsee Pannu), a lawyer married to Murad Ali’s son, takes on an utterly biased prosecution, which is out to declare the entire family guilty of the heinous crime.

Unfortunately, Pannu springs to life only during the climatic defense argument, which swings between justice and religion, between truth and prejudice. The director dumps just about everything on Kapoor’s shoulders.

Kapoor gives a fine portrayal of disappointment and sorrow – whose transformation from a romantic hero (“Bobby”) into unbelievably inspiring characters (as in “D Day,” “102 Not Out” and now “Mulk”) is what cinematic legend is all about. He helps push the well-crafted narrative with feeling: “Why must I prove my patriotism? This is my country,” is his heart-rending cry.

”Mulk” comes as a whiff of fresh air from the Bollywood stable, often criticized for being a shallow song-and-dance show.

‘Mulk’ takes a disturbing look at Islamophobia in India

‘Mulk’ takes a disturbing look at Islamophobia in India

- A brutal look at the kind of Islamophobia now sweeping across the world

- Kapoor gives a fine portrayal of disappointment and sorrow

Yazan Halwani unveils ‘The Memory Tree,’ commemorating Lebanon’s Great Famine

- Halwani’s work has matured significantly since he first embraced calligraffiti in his teens

- His aim is to help create an art scene — and market — in Lebanon that can flourish

DUBAI: “The most important aspect of art is that it pushes people to think, right?” asks the Lebanese artist Yazan Halwani. “To think critically.”

Halwani is walking through the streets of Beirut as he talks on the phone, posing questions and offering answers. The sound of the city — people, cars, industry — can be heard clearly in the background as he talks of individual and public narratives.

Originally a street artist, Halwani’s work has matured significantly since he first embraced calligraffiti in his teens (he is only 25 now), merging Arabic calligraphy with graffiti art. Back then he sought to solidify the link between the people of Beirut, their culture, and the Arabic language, creating popular murals of Fairouz, Asmahan, Khalil Gibran, Mahmoud Darwish and Ali Abdullah — a homeless man who used to live on Beirut’s Bliss Street. For Halwani, the true icons of Lebanese society were cultural or artistic, not political.

They still are, although his focus has recently shifted more toward ambitious public projects, which are few and far between in Lebanon. Of all his murals, it is the Eternal Sabah, painted across one entire side of the Assaf Building in Hamra, that is most strikingly visible.

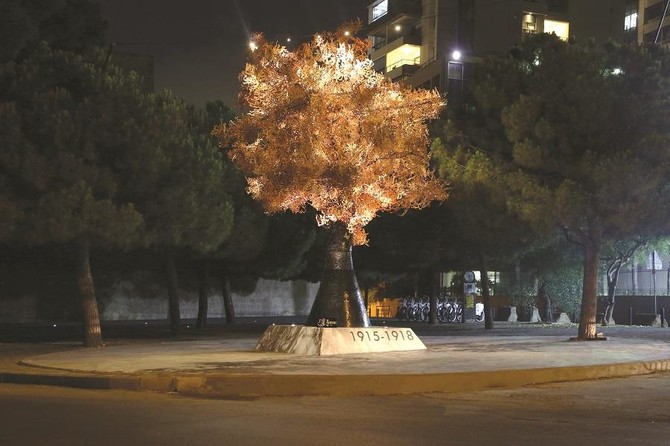

Now he has embraced public sculpture for the first time, creating a permanent monument to the Great Famine of Lebanon. Standing eight meters high, made of painted steel, and weighing more than two tons, The Memory Tree — commissioned by the Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth and writer Ramzi Toufic Salame — commemorates the estimated 200,000 people who died in the famine between 1915 and 1918. It is the first memorial to ever be erected to the disaster.

The tree’s ‘leaves’ are actually Arabic calligraphy. It took Halwani (working alongside two metalworkers) a year-and-a-half to complete. It is an incredibly complex piece of work, with each leaf forming the words of revered writers contemporary with the famine, such as Tawfik Yusuf Awwad and Khalil Gibran, whose poem “Dead Are My People” was dedicated to the famine’s victims.

“I always have experimental projects in my studio, some of which are related to sculpture, but I’d never done anything close to this scale,” admits Halwani. “It was extremely difficult, but given that the visual language I used — the calligraphy, the way the composition is done, the colors — was quite in line with my murals and paintings, it felt at times like I was composing a multitude of two-dimensional surfaces.

“The calligraphy, however, was very different to what I used to do. When I started painting I wanted to break the traditional rules of Arabic calligraphy and I used it abstractly,” he continues. “Calligraphy used to be a pixel of a painting — I didn’t write anything, the meaning was in the image. In this monument, it’s more in line with the traditional use of Arabic calligraphy. It’s words and writings.”

Although there is a fluidity of visual language between Halwani’s murals and the sculpture, which was funded by the Central Bank of Lebanon and is located in a plaza on Damascus Road, the memorial is also instructive. It highlights a central problem: Lebanon does not do national monuments.

Lebanon seems to suffer from collective amnesia, much of it state-sponsored. There is no memorial to the civil war, for example, despite its immense impact on the country and its people. And the fact that it took 100 years to publicly acknowledge a famine that killed around half of the country’s population says a lot about public discourse.

“The main issue in Lebanon is that each person within their small group — whether that’s a sect, area or religion — has their own narrative,” says Halwani. “There’s no national conversation. This is why such a monument is so relevant. It creates a conversation that is honestly overdue.”

Conversations are important to Halwani. His older art sought to reclaim Beirut’s streets from the clutches of the city’s myriad political parties, triggering a debate around public space and the country’s sectarian political system. He views narratives relating to public memory as instrumental to both national reconciliation and identity, and is determined to democratize art in Lebanon. In short, his work is intensely political, even if not outrightly so.

“There has never been a Lebanon with institutions that function — a Lebanon that really cares about a long-term democratic project,” says Halwani. “This is something that needs to be addressed from the political side, the economic side, and the cultural side. This is why personally I do not adopt the stance of just being an artist. There are many roles to be played and I’m not exclusive to just the cultural side. Because at the end of the day, if you’re only an artist you become a victim of the existing power structure if you don’t have the financial independence and the mobility to escape it.”

The first time Halwani and I spoke was in 2015 while he was still studying computer and communication engineering at the American University of Beirut. Now he is weeks away from swapping Beirut for Harvard University and a master’s in business administration.

His aim is to help create an art scene — and market — in Lebanon that can flourish, one that is “for artists to have long-term careers purely focused on creating artwork that’s recognized on the international scene.”

“I started with graffiti, which is not the most intellectual or critically acclaimed art form,” he says. “But I think the most important thing that I’ve always done is try to find something that resonates. Something that’s contemporary. You need to get the feel of the people around you. So when you place an artwork in the street, you don’t look at how beautiful the artwork is, you look at how the people look at the artwork. I don’t necessarily see the object or the paint on the wall, but rather how it reflects with the people.

“This is why there are some artworks that are technically very bad, but as public artworks are really successful. The Fairouz mural, for example. Painting-wise, I’m ashamed of it. Yet it is the piece of work that resonates most with people, mainly because of where it is, how it integrates into the landscape around it, and because it’s Fairouz. But also because it was a spontaneous reaction to political posters being stuck on the walls of Beirut.”

The Fairouz mural is still clearly visible in Gemmayze, although a window has been built into it — a commercial decision that could be considered artistic vandalism.

It was not the first piece, and no doubt won’t be the last, of Halwani’s work to be damaged or defaced. During this year’s parliamentary elections the political campaign of Nadim Gemayel stuck posters over a mural of Khalil Gibran, an act that did the politician more harm than good. After a public outcry, the campaign issued an apology and Gemayel himself asked Halwani to repaint the mural. He refused.

“I find it extremely powerful that, because the people have a vision of how their public space needs to be, they have a reaction and want to protect a piece of artwork,” says Halwani. “The political campaign actually cleaned up the wall, although it’s a bit damaged. But I think it should stay damaged. Just so this narrative remains.”