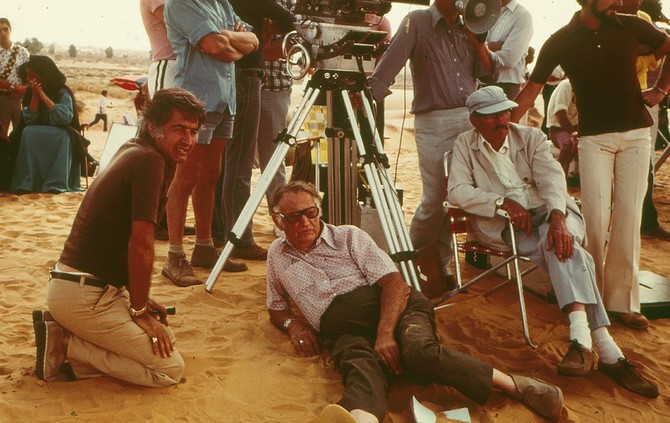

DUBAI: “I really had no idea how long the process that I was getting myself into would take,” admits film producer Malek Akkad. “The English version is three hours long and the Arabic version is three hours and 20 minutes. So restoring films of such length is very time consuming. But it was a labor of love and a very nice way to get deeply reacquainted with my father’s beautiful work.”

Akkad’s father, of course, was the late film director Moustapha Akkad, whose 1976 masterpiece “The Message” was screened in Saudi Arabia for the first time over Eid-Al-Fitr. Chronicling the life of the Prophet Muhammad and the birth of Islam, it has been lovingly restored to 4K quality — a process overseen by Malek — and was passed for screening in the Kingdom by the General Commission for Audiovisual Media on June 7.

Bringing such a controversial film back to life has not been an easy task. “The Message” met with a wave of controversy when it was first released and was banned across the majority of the Arab world, including in Saudi Arabia. It was also rejected by the Muslim World League in Makkah and described as “an insult to Islam” by scholars in Cairo. Kuwait continues to ban the film.

“Ironically, even though it’s over 40 years later, probably the biggest challenge has been, once again, all the censorship boards and trying to get them to come around and see this film in a new light,” says Akkad. “Over the years it’s become a favorite, a classic in the region that they play on satellite stations, so a huge portion of the population is very familiar with this film. But there’s still some of the old guard at the censorship boards. But I’m happy to say we’ve been pretty much successful in a large number of countries and I’m very happy about that.”

That the film finally screened in Saudi Arabia, the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, after 42 years is particularly pleasing to Akkad. Saudi Arabia was one of the most vocal opponents of the film when it was being made, with political pressure from the Kingdom leading to the loss of the film’s Moroccan sets and the relocation of filming to Libya six months into production.

“I would ask my father a lot of things about the making of the film, but he was such a humble man he never really talked about himself,” Akkad says. “But from my digging and research I understand there was a time when Saudi Arabia was supporting it — well before they started shooting — and then they had to back out for various reasons. And that’s really the most amazing story about this. Because every obstacle put in my father’s way, he just persevered and overcame them with just the most calm and confident demeanor.”

Born in Aleppo, Syria, Moustapha Akkad began filming “The Message” in 1974, shooting two versions simultaneously — one in Arabic and one in English. The Arabic version featured some of the biggest stars of Arab cinema, including Abdullah Gaith in the lead role of Hamza and Muna Wassef as Hind, a Makkhan woman who initially opposed the Prophet’s forces but eventually embraced Islam. In the English version, the role of Hamza was played by Anthony Quinn, while Irene Papas portrayed Hind.

In accordance with Islamic beliefs, Prophet Muhammad was not depicted on screen, nor was his voice heard. Neither were his wives, his daughters or his sons-in-law heard or seen. In the completed film, actors speak directly to the camera and then nod to unheard dialogue.

An admirer of the British director David Lean, Akkad’s goal had been to create an epic film in the vein of “Lawrence of Arabia” or “Ben-Hur,” with his primary motivation being the fostering of greater understanding between the Western and Islamic worlds. Filming took over a year to complete and was plagued by setbacks.

“What amazes me most about these films, year after year, is just the enormous effort that he went through to produce and direct these movies,” says Akkad. “It was a Herculean, Sisyphean task against all the odds. I’m a producer and director now and I know how tough any film production is, but this was just on a whole different level.”

The restoration process began over two years ago, with each individual frame having to be scanned at 4K quality and then color corrected. A 5.1 surround-sound mix was also created. It was an undertaking that involved numerous companies across the US and the UK, with the final restored versions of the film having their world premieres at the Dubai International Film Festival last December.

“I’m not necessarily sure if his original goal was to become what he became — which was an ambassador or spokesperson for the entire Arab and Islamic world — but what he saw in the States at the time was really a deep misunderstanding of what Islam is and even where the Middle East was,” says Akkad. “It was a very inward-looking time for the country and he jumped right into the fray as a student activist, holding fairs and workshops to try and explain where he came from.

“When he made the film it was a time of misunderstanding between East and West and, sadly it seems, it’s now more a case of antipathy than misunderstanding. And that’s sad. It seems like we’ve gone backwards.

“My father’s belief was that with cinema we could share common stories and revel in the differences that we have and enjoy them. He was very much a man of the world and loved people of all religions and cultures. No one film can solve any of these big worldly issues we’re facing. However, I do feel that The Message was a huge step towards that,” he continues.

“That’s why I hope this release can remind us all that we are all in this together. Islam is practiced by a third of the world’s population and, especially in the West, if we took the step to be more understanding — or to try to be — we might know the other a little bit better, and that would be a wonderful thing.”

Although The Message was his greatest undertaking, Akkad is perhaps best known in the US for something completely different: producing the original series of Halloween films. It is a role that his son has continued, with the 11th installment of the franchise set for release this year.

Tragically, Moustapha Akkad and his daughter Rima Akkad Monla were both killed in the 2005 Amman bombings.

“My father did not have the chance to see this fulfilled in his lifetime, but I know he would be very proud of this moment,” says Akkad, who is also producing a documentary on the making of “The Message.”

“This is a tribute to him. He wanted to share his love of this culture and the important lesson of Islam and “The Message” with everyone. Now, at a time when the world most needs it, his dream will come alive.”